Max Littman, LCSW

August 11, 2025

Karl Marx described alienation as the condition in which workers are estranged from the products of their labor, the process of production, their fellow workers, and ultimately themselves. Under capitalism, production often happens at a scale and under conditions that disconnect people from the meaning, satisfaction, and communal reciprocity that work once held.

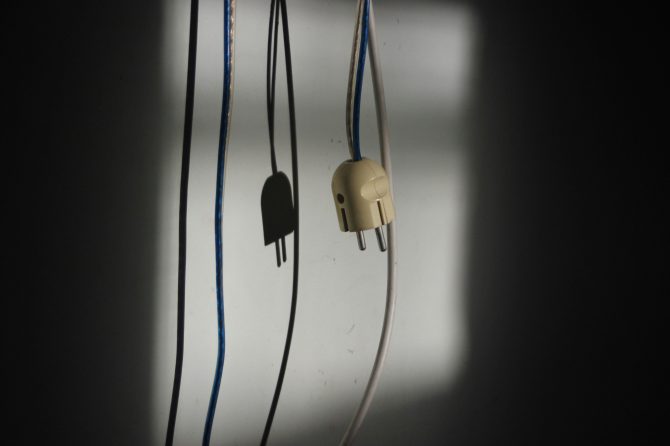

Today, we’re living through a parallel alienation—one not just from our means of production, but from our means of connection. The same economic forces that once stripped away the intimacy of making and trading goods now find their echo in technologies that strip away the intimacy of living, relating, and belonging in embodied community.

The Rise of Disembodied Life

Technology’s spread has brought profound conveniences, but many of these advancements share a common trait: they bypass the body. AI, smartphones, streaming, and delivery systems let us acquire, consume, and communicate without engaging our senses beyond eyes and fingertips. With this modern consumption, our bodies become passive recipients instead of active participants in connection.

We stream a concert rather than stand in a crowd feeling the bass in our ribs.

We order dinner with a tap instead of smelling the spices as they fill a restaurant’s air.

We chat in a thread instead of sensing a friend’s microexpressions or the cadence of their breathing.

What’s being sold is still “connection” or “experience,” but the process no longer involves the human presence that once defined those things.

Alone Together in Public

Walk through any city, ride public transit, or sit in a waiting room, and a clear pattern emerges: most people are physically present but mentally elsewhere. Eyes fixed on phones, ears sealed by earbuds, we drift through shared spaces without acknowledging the strangers beside us.

This is not simply about etiquette or nostalgia—it is about the slow erosion of the unplanned, serendipitous interactions that have long been part of public life. Before smartphones, a bus ride might involve overhearing a conversation that made you think differently, or exchanging a few words with the person next to you. A park bench might host a spontaneous chat that led to friendship. Even silent coexistence—reading a book, daydreaming, watching the world—kept us open to the small invitations of the present moment.

Earbuds and screens create a private bubble in public space. The world outside becomes muted, peripheral, secondary to the curated feed or playlist inside the bubble. In the short term, this can be a welcome escape from overstimulation or unwanted attention. But over time, the habit of retreating into digital space whenever we’re in public weakens our capacity to engage in—and be shaped by—the unpredictable texture of real-time, face-to-face encounters.

We are, in many ways, “alone together”: bodies sharing space, each tethered to an elsewhere. The cost is a shrinking sense of the public as a living, relational environment.

Pandemic as Accelerator

COVID-19 supercharged this disembodiment of community. Lockdowns and distancing measures gave rise to telehealth, remote work, Zoom celebrations, and livestreamed rituals. For many, these kept us afloat. For others, they became replacements rather than stopgaps. The transition back to embodied connection has been uneven and, in some communities, hesitant.

Telehealth, for example, widened access to care but also shifted therapy, medicine, and even somatic healing into tiny rectangles. We learned to communicate the most intimate aspects of our lives while sitting still, staring into a camera, cut off from the subtle shared space that arises in person.

AI and the Further Automation of Relationship

Artificial intelligence now threatens to industrialize connection itself. AI “companions” promise constant company, but at the cost of replacing relational complexity with programmed responsiveness. Customer service lines, once staffed by people, are now chatbots. Content that once emerged from lived human experience is increasingly generated by predictive models.

The more we accept AI as a stand-in for human relationship, the more our expectations for real connection are shaped by what AI can provide: immediate responsiveness, minimal discomfort, and the illusion of intimacy without mutual vulnerability.

Social Media and the Performance of Connection

Platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and X market themselves as tools for staying connected. But much like how capitalism turns production into a commodity, these platforms turn sociality into content. We share moments not for the experience of them, but for their exchange value—likes, views, follows.

The body becomes a brand. Friendship becomes a feed. Intimacy becomes performance. And all the while, the algorithms keep us scrolling, less aware of the people in our actual, physical vicinity.

Streaming, Delivery, and the End of the Marketplace

Historically, marketplaces—whether literal stalls or neighborhood shops—were sites of both commerce and community. You didn’t just buy bread; you spoke with the baker. You didn’t just pick up vegetables; you exchanged news with neighbors.

Streaming platforms have done to entertainment what Amazon has done to commerce: removed the shared spaces where these transactions used to occur. DoorDash, Instacart, and other delivery systems collapse the messy, relational aspects of shopping and dining into a frictionless, contactless transaction. The buyer and seller never meet; the community between them never forms.

From Shared Screens to Saturated Streams

There was a time when television, music, and film were fewer in number but greater in collective impact. A single show could stop conversations the next day because everyone had seen it. A new album release could ripple through an entire town. A film could linger in theaters for months, allowing swaths of people to experience it in real time and talk about it together—in schools, at work, on street corners. The scarcity of content meant that when something hit the cultural zeitgeist, it created a shared language, a common point of reference that knitted communities together both locally and nationally.

Today, we have the opposite problem: an unprecedented proliferation of content. Streaming platforms, digital music services, and on-demand film libraries have broadened representation in ways worth celebrating—offering voices, stories, and perspectives once excluded from the mainstream. Yet the sheer abundance has also fractured our cultural landscape. With so many options competing for our attention, it is harder to find people who have experienced the same piece of art, much less at the same time.

Even when we want to share something meaningful—a film that moved us, an album that changed us—the act of passing it along often lands as a burden. “I’ll try to get to it,” becomes the polite default, not because the recipient isn’t interested, but because they are already drowning in a constant influx of content, notifications, and personal obligations. What was once a point of instant connection now risks becoming another item on an endless to-do list.

In this environment, art still has the power to connect us—but the connections it sparks are harder to sustain. Without shared moments of cultural attention, the communal conversations that once flourished around art have grown quieter, replaced by countless parallel but unshared experiences.

Corporations Without People

Increasingly, we interact not with humans, but with corporate infrastructures. When something goes wrong with a product or service, there’s rarely a local owner to speak with—only an anonymous form or outsourced call center. The more powerful the corporation, the less visible the people within it. This anonymity mirrors Marx’s critique: under capitalism, the worker’s humanity is hidden behind the commodity. Now, even the human in the interaction is hidden, replaced by systems that keep us at a remove.

The Weaponization of Disconnection

Disembodied life also makes us more vulnerable to manipulation. The same technologies that promise connection have become powerful engines for misinformation, political polarization, and the rise of authoritarian movements.

Without the grounding of an embodied community—without seeing and hearing people in real life—we become easier to sort into ideological camps. Social media platforms reward outrage over nuance, certainty over complexity, and dehumanization over dialogue. Algorithms feed us content that confirms what we already believe, deepening echo chambers until we can no longer imagine the humanity of those outside them.

This dynamic has created fertile ground for modern fascism. Leaders and movements that thrive on division no longer need to rally people in the streets; they can inflame, organize, and radicalize from a screen. In the process, political identity has become a primary lens through which many people view the world—not just for civic issues, but for every facet of life. Brands, friendships, sports teams, even public health practices become politicized, making every choice a declaration of allegiance.

When everything is politicized, disagreement becomes existential. Instead of grappling with difference, we see others as threats. Instead of building coalitions to address shared problems, we retreat further into our chosen silos.

Embodied community resists this fragmentation. When we sit across from someone and share a meal, or work on a shared project, it becomes harder to flatten them into a caricature. Without such grounding spaces, the current of politicization will continue to pull us apart.

The Cost of Disconnection

This disembodiment and automation erode our capacity for communal resilience. Historically, communities have survived crises not through sheer self-reliance, but through reciprocal care: shared meals, physical presence in grief, neighbors looking out for one another. The less we practice embodied connection, the less muscle memory we have for it when it’s most needed.

The cost is also personal. Our nervous systems are shaped by co-regulation—by the subtle dance of attunement that happens face-to-face, breath-to-breath. When most of our “connections” are mediated by screens, we lose access to that regulating force, leaving us more anxious, more isolated, and paradoxically more dependent on the very technologies that contribute to the alienation.

The Inner System in an Era of Disconnection

From an Internal Family Systems (IFS) perspective, the cultural disembodiment and alienation we’re experiencing don’t just live “out there” in the world—they live in our internal systems. The pressures, overstimulation, and isolation of modern technological life pull certain protectors into the lead and deepen the burdens our exiles carry.

Managers adapt by trying to keep us safe, productive, and socially acceptable in an environment that often rewards speed, image, and digital presence over slow, embodied connection. They may push us to curate our online identity, monitor news feeds for perceived threats, or avoid vulnerability in favor of polished self-presentation.

Firefighters step in when the loneliness, anxiety, or overstimulation pierce through the managers’ control. They might binge streaming content, scroll endlessly, drink, shop online, or retreat into immersive digital worlds—anything to dampen discomfort quickly, even if it deepens the disconnection in the long run.

Meanwhile, exiles carry the grief, longing, and shame that arise from our loss of embodied belonging. They may remember a time when community felt easier or more natural, or they may hold the ache of never having truly felt it. The cultural conditions of isolation, polarization, and constant noise often confirm the exiles’ fears: that intimacy is unsafe, connection is fleeting, and no one will show up in the ways they need.

Over time, these dynamics can become self-perpetuating burdens. The more disconnected we are, the more our exiles ache, and the more our protectors turn to the very technologies and habits that keep connection at bay. In this way, the societal architecture of disembodiment becomes mirrored inside us, shaping our daily choices and even our sense of ourselves.

Recognizing this parallel allows us to meet not only the cultural forces but also our internal responses with compassion. It invites our protectors that keep us cycling through digital escape to unblend from our Self, which allows us to offer our exiles the kind of embodied presence—eye contact, shared space, touch, attunement, resonance—that they have been missing.

Grieving What We’ve Lost to Disconnection

Francis Weller describes grief not as an obstacle to living, but as a vital nutrient for the soul—a way of metabolizing loss so that we remain available to life. In The Wild Edge of Sorrow, he names “the gates of grief,” among them the sorrow for what we love but never truly received, and the grief for the losses we share collectively.

When we look at the technological unraveling of an embodied community through this lens, we can begin to see the quiet, unspoken grief that runs beneath our everyday lives. We grieve the gatherings that have thinned to pixels on a screen. We grieve the shared meals we no longer linger over, the street corner conversations now replaced by doorstep drop-offs. We grieve the loss of a commons—a physical, relational space where our lives could touch and shape one another without an algorithm mediating the exchange.

Much of this grief is unacknowledged.

It accumulates as a subtle ache: the low-grade loneliness after a night of scrolling, the inexplicable emptiness after a day filled with “virtual” meetings, the sense that something essential is missing even when all our needs appear met. Weller warns that unexpressed grief calcifies into despair or numbness. Left unattended, it can trick us into thinking that the absence of embodied community is normal, inevitable, or even preferable.

Ritual, in Weller’s view, is how we transform grief from a weight we carry alone into a shared act that reconnects us. In the face of technological disconnection, grief rituals—whether formal or improvised—become acts of resistance. Gathering in person to mourn what we’ve lost is itself a reclamation of community. Singing together, making food for one another, creating art in response to our shared losses—these are ways to honor what’s gone while weaving ourselves back into the fabric of human presence.

To live without naming or tending to this grief is to accept the slow erosion of our humanity. To grieve it is to remember that what we are losing matters—and that by remembering together, we can begin to reclaim it.

Toward a Re-Embodied Future

This is not a call to abandon technology wholesale. It is a call to notice where it replaces rather than supports an embodied community, and to choose differently when we can. It’s a call to meet a friend in person instead of defaulting to text. To shop at a farmers’ market, local bookstore, or family owned shoe store instead of relying solely on delivery. To attend a local concert instead of streaming one alone.

Re-embodiment means valuing the inconvenient, the inefficient, the unscalable. It means resisting the logic that the fastest, most frictionless option is always best. And it means remembering that connection—real connection—is not a commodity. It is a practice and an essential nutrient to human life.

If capitalism alienated us from our means of production, today’s technologies risk alienating us from our means of being. The antidote is not nostalgia, but a deliberate weaving back together of what disembodiment has frayed: the shared spaces, sensory presence, and human-to-human contact that make life more than a transaction.

Grief as a Bridge Back to Connection

If capitalism’s alienation severed us from our means of production, and modern technology now severs us from our means of connection, grief may be a bridge that can link us back. Marx called for a reclamation of the worker’s agency and relationship to the work of their hands; Weller calls for a reclamation of the human soul’s agency and relationship to the work of our hearts.

Both require a refusal to normalize estrangement. Both demand that we see clearly what has been taken—not to stew in resentment, but to awaken the longing for something whole.

Grieving together for the loss of an embodied community is not a sentimental act. It is a radical one. It refuses the story that disconnection is simply the cost of progress. It refuses the shrinking of our social imagination to what a device can mediate. It invites us to remember that we were made to touch, to sing, to sweat side by side, to be altered by one another’s physical, embodied presence.

When grief is recognized and allowed to flow, it does not just mourn the past; it clears the ground for the future. It softens the walls around our hearts, making us more willing to reach out, to rebuild the commons in whatever ways are possible here and now, to stay in contact with each other through tough times. If alienation is the withering of our relational soil, grief is the rain that can make it fertile again.

In this sense, tending to our grief for lost community is not separate from resisting technological alienation—it is the very heart of embodied and loving resistance.

For feedback and comments, I can be reached at max@maxlittman.com.

I provide private practice mentorship, consultation, and therapist/practitioner part intensives.